Next episode

| Breakaway

Commander Koenig is sent up to take control of Moonbase Alpha after a

mysterious virus scuppers a vital space probe mission. He discovers that

magnetic energy from the nuclear waste dumps is responsible - but before he can

sort the problem out, the nuclear waste explodes and blasts the Moon out of

Earth's orbit... | |

Attention All Sections Alpha:

A spacecraft travels from Earth with a single VIP passenger, on his way to the Moon

base to take charge of the investigation into an inexplicable mystery. It's 2001: A

Space Odyssey! I don't think there can be any doubt that the opening of Breakaway

is riffing on the Kubrick masterpiece. There's even a stewardess on duty. (Koenig doesn't

fall asleep and let his pen float off weightlessly though...) If you want further evidence,

just look at the opening shots of both productions: a line-up of the Sun, the Earth and the

Moon. It's hard to say whether all this is a deliberate homage or an unconscious echo - but

it's immediately obvious that 2001 is a major influence on the look and style of

Space: 1999.

In fact, I'd go further than that and suggest that Space: 1999 is a conscious

attempt to create a television equivalent to 2001. (Even the title is practically

the same!) [And it was this very fact which led Stanley Kubrick, in one of

his more fevered moments, to seriously consider suing the producers for damages.]

It's easy to spot those elements of the first series which derive in some way

from that movie: visual cues such as the exterior design of the Moonbase and the

brightly-coloured spacesuits; the style of the special effects (which effects designer

Brian Johnson was deliberately attempting to reproduce); and such stylistic and

philosophical conceits as the underplayed characterizations, and the theme of humans forced

to confront the mysteries of outer space head on, at the mercy of inconceivable higher

powers who shape their destiny. These borrowings, whether conscious or otherwise, are not

necessarily a bad thing. They say if you're going to steal, you should steal from the best!

2001 had completely changed the look of science fiction, and redefined the

audience's conception of outer space. [This huge leap forward in the

visual aesthetic completely overwrote the look of 1950s films by directors like George Pal

(which had themselves influenced the look of earlier sci-fi television - you can't watch

the launch sequence of Fireball XL5 without thinking of When Worlds Collide

for instance). We wouldn't see anything as radical again until Star Wars.]

So, having a whole new set of visual influences might be one reason why Space: 1999

seems so different to the earlier Anderson shows. Another, more obvious explanation is that

different people were working in the key visual design roles. Long-term collaborators Bob

Bell (production design) and Derek Meddings (special effects) had moved on to other

projects, and both been replaced by their former assistants. Keith Wilson and Brian Johnson

bring a completely new visual style with them. But more than that, there's a sense that

everyone is at the very top of their game. [Case in point: there's no

question that Barry Gray is a brilliant composer, and has been providing memorable themes

for Anderson for years, but he's always had a tendency to lapse into writing "humourous"

children's tv music - even as recently as UFO. There's none of that here.] They've

been given a lot more money than they've ever had before, and they're really going to make

the most of this opportunity. This is what Gerry Anderson has been building up to for

years. (And that, really, is the significance of the lineage of Gerry Anderson productions:

those earlier shows were the proving ground that got him into the position where he could

make Space: 1999.) [No, seriously. There's such a massive stylistic

shift in the look of Space: 1999, it's simply impossible to think of it as part of

an ongoing series. It's such an odd notion, that of the "Gerry Anderson production" being

almost a genre in itself, but that's the way a lot of people seem to think of it, rather

than as a number of discrete, disparate programmes that happen to have been produced by the

same man over the years. Anderson was always a master at brand marketing (years before

George Lucas thought of it...) and one brand he managed to sell was that of Gerry Anderson

himself. He is surely one of the few tv producers ever to have his own fan club. (As

opposed to having fans of his specific works - I mean, an X Files fan might decide

to check out Millennium, but I think they'd be unlikely to declare themselves a

"Chris Carter fan".) The very existence of Fanderson is built on the notion that you can

give equal weight to Space: 1999 and Torchy the Battery Boy, which is patently

absurd. Alright, I'm not oblivious to the fact that there's a certain stylistic and design

aesthetic whose development can be traced from Four Feather Falls all the way to

UFO, and that's largely for the same reason that Space: 1999 seems so

different - more or less the same creative team is behind all those series. Later Anderson

shows, such as Terrahawks or Space Precinct, are much easier to regard as

standing apart from the past - I suppose I'm just arguing that Space: 1999 should be

viewed as the first such stylistic departure.]

Anderson does seem to have gone out of his way to make Space: 1999 stand apart from

his previous shows. For a start, he hired completely new writers. (A couple of them had

written scripts for The Protectors, but not for any of his earlier sci-fi efforts.)

Though there was certainly some insistence from the show's US backers to have American

writers involved, that doesn't seem to have been Anderson's motivation here. (In any case,

that didn't work out in practice - the difficulties of trying to hold trans-Atlantic script

conferences put paid to that - how much easier it would have been with email and video

conferencing! - ultimately they restricted themselves to using a few American writers who

were already based in Britain.) In fact, the process had already started in 1972, when

Anderson hired Christopher Penfold as story consultant (at the time, to help devise the

format for a planned second series of UFO - but this project eventually metamorphosed

into Space: 1999). In retrospect, it seems an odd choice. Remember, Anderson had

built his career on forming the right creative team and then working with them from series

to series. You have to wonder why Anderson didn't turn to his regular script writer Tony

Barwick, who'd written vast swathes of Captain Scarlet, Joe 90 and UFO

(and would later pen most of Terrahawks), rather than Penfold who'd never worked

with him before - unless it was for the sake of trying to forge something completely new.

The credited writer of Breakaway, George Bellak, was one American writer who did come to

Britain to work on Space: 1999. Originally hired as a script editor to work

alongside Penfold, Bellak left the production soon after completing this script (by all

accounts, there was something of a clash of personalities between him and Anderson). With

only this one script credit to his name, Bellak is something of an unsung hero of Space:

1999. Christopher Penfold gives him credit for much of the show's style and philosophy.

Working together, the two writers refined the format and wrote the series bible. Following

Bellak's departure, Christopher Penfold rewrote the opening script. The original version

entitled The Void Ahead was intended to fill a ninety minute slot, rather than the

standard television hour of the finished episode. Though it essentially tells the same

story, many of the supporting characters had yet to finalized; there were also a number of

additional scenes which filled in character detail - most notably a sequence where Gorski

visits Koenig to rubbish Helena's theories about the "infection"; and a scene where Helena

explains the reason for Gorski's animosity - that he made a pass at her which she didn't

reciprocate. I'd always wondered whether these scenes were cut at script stage,

or filmed and then dropped in editing. If the latter, it might explain why an actor of

Philip Madoc's calibre was engaged as Gorski, a character who amounts to a twenty-second

appearance in the finished episode.

It's certainly been reported that the shooting of Breakaway far exceeded its

original schedule. Lee Katzin was an American director brought in at the insistence of the

US backers; he had plenty of experience in series television, including technically

complex shows like Mission: Impossible (on which he'd worked previously with Landau

and Bain of course), so was considered a safe pair of hands to launch Space: 1999.

No one seems quite sure why he made the unprecedented decision to shoot excessive coverage

of every scene, with multiple angles and reaction shots. (I like to think that he became so

enthused by the concept of Space: 1999, he forgot he was shooting television and

decided to treat it as a feature film.) Katzin ended up with a rough cut reportedly some

two hours long. Seemingly, it was left to Gerry Anderson to shoot some pick-ups and then

edit the whole lot down to the required fifty minutes. Whatever the truth of the matter,

the tension and pacing of the finished episode is remarkable.

[Whereas Anderson's true talent as a producer has always been

as a manager, having the ability to hire the right people to do the job, I think his real

creative skill has been as an editor and director.] It would be interesting to see

some of Katzin's discarded footage - (presumably those scenes of Gorski among them) - but

as no deleted scenes package turned up on the DVD, it seemed unlikely that the rushes had

survived. And yet, amazingly, in November 2010, several reels of audio tape surfaced

containing raw studio sound from the filming of Breakaway. [Which

just goes to show, you never know what might still be out there somewhere.] Although

obviously lacking the visuals, these recordings offer a fascinating insight into a work in

progress. There are a lot of dialogue fluffs and actors missing their marks, and almost

continual retakes - plenty of evidence of the huge amount of coverage that Katzin shot.

As well as scenes that never made it to the final cut, many of the other sequences are

quite different to what we eventually saw, indicating that much of the finished

script was amended during production. There's also plenty of material that's simply

unnecessary, repetitive and saggy scenes that would have slowed the pace right down

- there's no doubt that the decision to cut was the right one. (And yes, in answer to

my question, there are several takes of that scene between Gorski and Koenig, the

characters exuding a mutual loathing.) [These audio clips have been

posted to Youtube, and are well worth seeking out - do a search there for "Space 1999 rare

audio".]

The exterior design of Moonbase Alpha, a complex of mainly low-lying buildings

radiating from a central hub in a circular arrangement, is very similar to Clavius Base in

2001. We only saw the briefest glimpse of the interior of Clavius - the conference

room where Floyd briefed the scientists. (Although there were cut scenes that would have

shown it to be a far less austere place than Alpha; for instance, the base personnel would

have had their families with them.) As the regular setting for all 24 episodes, it's

inevitable that we get to see a lot more of the interior of Alpha. Keith Wilson devised a

modular system of wall panels and set elements (like a giant Lego set) meaning that

different rooms and corridors could be constructed quickly as required for each episode -

various labs, offices and living quarters. (One criticism I've seen is that the medical

centre looks different in each episode. Personally, I don't see why this is a problem -

it's not a small ship's sickbay, it's a hospital with many different wards.) The main

standing set is the massive complex of Main Mission and the adjoining command office.

Unusually for television scenery, this creates a true sense of scale; and this really sums

up Wilson's work on Space: 1999 - it looks big. The design of Alpha is sleek and

futuristic (which is ironic given that the series is now set in the past!) and believably

consistent - even the plastic desklamps and moulded garden furniture seem to fit in with

the design statement, rather than being the cheap cost-cutting measures they obviously

were.

Gerry Anderson's shows are justifiably famous for their special effects. For years,

Derek Meddings pioneered filming techniques that were streets ahead of what the cinema was

doing. It was inevitable that he would end up going into the movies. [And

yet, much as it pains me to say this, I always find there's a strange artificiality to all

of Meddings's work - no matter how accomplished the effects are, the models look like

models. Whether it's the lighting or the detailing, I couldn't say, but there's just

something that prevents me from suspending my disbelief. Now, this isn't so much of a

problem on the puppet shows, as the characters are artificial too! But it becomes just that

much more obvious when contrasted with the live actors in UFO. Let me just add,

Meddings's effects for the Bond films are perfectly fine.] For Space : 1999,

Anderson turned to Brian Johnson, who had been an assistant to Meddings on Thunderbirds,

as well as working on numerous feature films - including crucially 2001.

[Much was made in the publicity of Johnson's work on 2001, but I

think a lot of it was hype. He wasn't one of the film's credited effects supervisors

(indeed, he's not named in the credits at all) - and of course, the effects designer for

2001 was Stanley Kubrick himself. Johnson was working as a technician, mainly on the

lunar sequences - that explains the design of Moonbase Alpha, then! In terms of its

contribution to Space: 1999, I think the most important thing he did on 2001

was watch and learn what was possible.] Johnson was convinced that he could produce

effects of the quality that Kubrick had achieved, but on a television schedule and budget.

No one can question that he succeeded. Space: 1999's effects are the best modelwork

ever presented on television. Modern CGI effects may be more frenetic and colourful, but

there's a real depth and solidity to good modelwork that CGI hasn't achieved yet.

Johnson's effects have an almost monochrome signature look: white ships against black

space, that very much fit with the look of the series.

Moonbase Alpha is equipped with a fleet of Eagles, which we see here

functioning as shuttles and freighters - with a different central module for each purpose.

The Eagle is a triumph of design, and far more realistic than many of the outrageous craft

Derek Meddings dreamt up for the earlier Anderson shows. The basic shape is not

aerodynamic, which is fine for operating in the vacuum of the lunar surface. The modular

design - a cockpit at the front, engines at the back, held together by a framework of

girders to which the specific mission module is attached - is practical, and actually

similar to real proposed space freighter designs. [It also makes for a

brilliant toy. Detachable and interchangeable pods - that's what kids like. I'm serious.

Back in the days of Thunderbirds, Gerry Anderson believed that Scott would be every

boy's hero and Thunderbird 1 the most popular craft; of course, it turned out that everyone

liked Virgil best (because he did all the dirty work) and loved Thunderbird 2 - great,

unwieldy beast that it was. Why? Because it had a pod. A rocketship just flies fast from A

to B. But a pod has infinite play possiblities.] The Eagle design is also the basis

for other Earth spacecraft that appear in the series, which lends a certain degree of

conformity and believability to the development of the space programme.

As well as the usual passenger and freighter modules, the Eagle that shuttles

Commissioner Simmonds to the Moon has a unique orange pod, perhaps denoting that it has

special VIP facilities.

In an Anderson series, effects always mean huge explosions. [Just look

at the oil refinery that blows up in the Thunderbirds title sequence - it's only

there because it looks fantastic!] Breakaway features probably the biggest

explosion in the history of British television - the eruption of Disposal Area Two, that

blasts the Moon out of Earth's orbit. A building chain reaction of explosions culminates

in the whole waste dump being blown apart - before a fireball rises above the lunar surface

like the dawn of a new sun. It's an impressive sequence. The Space Dock also breaks free of

its orbit, and starts to spiral away before it blows up - presumably it's caught in some

kind of gravitational eddy. Compared to this, the earlier major effects sequence - the

flare-up of Disposal Area One and Koenig's Eagle crashing onto the lunar surface - seems

quite mundane, though the latter is superbly executed.

This is one of the four episodes for which Barry Gray composed a full score.

Breakaway's music is dramatic, successfully building up tension. Of particular note

are the low, throbbing strings that recur throughout the episode to accompany the scenes in

the nuclear waste dumps. They add to the sense of unease and impending menace.

[It's a trick Gray has used before, creating menace prior to the rock

snakes attacking the astronauts in Thunderbirds Are Go for instance; or when Foster

is lost on the Moon's surface with an Alien in UFO.] Gray's memorable theme

tune manages to be upbeat and contemporary (with, it has to be said, a really kicking funk

bassline) and a sweeping, classical composition at the same time - by the simple but

brilliant method of just alternating between the two styles.

The show's typography is of particular interest. Aside from the specially-designed title

logo, all the titles and credits are in the Futura Medium font. Like so many of the best

typefaces, this was designed in Germany in the 1920s - it's a sans serif font based on

geometric shapes. Its sleek, elegant simplicity make it very much part of the look of the

show. Interestingly though, the original intention was to use the variant Futura Black font

for the series title logo - a rather severe stencil-form typeface, it's retained for the

"This Episode" and "September 13th 1999" captions during the title sequence - and the

Braggadocio font for the cast and crew credits. This was apparently abandoned because it

rendered many names difficult to read. [And that's absolutely true: the

capitals aren't too bad, but the lower case letters in particular can be problematical. It's

no surprise it was dropped. What is odd though is they decided to go with Braggadocio in

the first place. Though it's superficially similar in appearance, Futura Black is a lot

cleaner, more elegant and easier to read; since they were using Futura Black in any case,

why not use it throughout instead of mixing typefaces like that?] Perhaps

significantly, Futura was the official font adopted by NASA for the Apollo project; it was

also used in the opening credits of - you've guessed it - 2001.

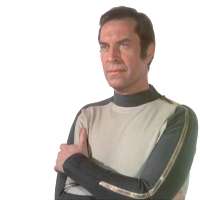

The acting is intense and mainly serious, the complex characters being sketched in

subtle shades of grey. (It's this which gets the series unfairly criticised for "wooden"

acting - although I suspect that started out as a "witty" joke about the Andersons' previous

shows using puppets. We're talking about acclaimed, award-winning actors here.) Martin

Landau's performance is intelligent and finely judged. Koenig immediately comes across as a

determined, instinctive man, but also concerned and basically honest; the main contrast

here is with Commissioner Simmonds, the nearest the episode gets to having a "villain".

He's an underhanded politician, smarmy and silken-tongued when he thinks it's necessary,

harsh and demanding at other times. Though it's fair to say that he behaves that way

because he's trying to keep the space programme running, he's still clearly a man more

concerned for his career than for the dangers to others.

Barbara Bain portrays Helena Russell as a totally professional and dispassionate

doctor. This is a bold acting choice, as it strips her character of the traditional,

feminine caring qualities that usually define a female doctor role, and makes it much

harder for the audience to like her. (Bain is certainly the one actor who comes in for the

most criticism of her "wooden" performance - even to this very day, when I think we're more

used to subtle characterizations on television. The thing is, I believe in Helena as the

chief medical officer of Alpha - effectively the head of a hospital - than I would a more

"touchy-feely" character like Doctor Crusher from Star Trek. There's more to being a

doctor at senior management level than having a pleasant bedside manner - although Helena

is kind and sympathetic with her patients as well; she's a character of many facets.)

The third lead is Barry Morse as Professor Victor Bergman. He appears to be our regular

scientific expert - here, for instance, he's the one who deduces the cause of the trouble

in the Waste Disposal Area. Morse imbues the character with real warmth and subtle humour.

Looking at the way the characters and their relationships start to develop in this episode,

it seems as if Bergman acts as a counterpoint to the tense and hard-nosed Koenig and the

emotionally repressed Helena. [It's interesting that these characters form

a sort of triptych, which in some ways mirrors that at the heart of Star Trek -

ironic in fact, given how much Star Trek's characters were held up as the exemplars

against which Space: 1999's "wooden" leads should be judged. Bergman fufils much the

same role as Doctor McCoy, acting as the human heart of the relationship, and the fulcrum

between the two extremes. Helena thus equates to Mr Spock, although Koenig doesn't really

match up to the comic book action hero role of Captain Kirk, and I'm afraid that's where

my analogy breaks down...]

Of the supporting cast, probably the most popular with the original viewing audience

was Nick Tate who plays chief astronaut Alan Carter. The character was originally devised

as an Italian called Alfonso Catani - and appears this way in Bellak's original script.

[This was partly because the Italian network RAI was putting up some of

the funding for the show, and insisted on Italian actors being featured. Apparently,

Giancarlo Prete was cast as Catani, but was contracted to a feature film and unable to make

the filming dates. Eventually, Prete played a guest role in The Troubled Spirit.

Several other Italian guest stars appear in later episodes, fulfilling the demands of

RAI.] Tate was originally cast in the role of Collins, but so impressed Lee Katzin

with his energy and aggression he was promoted to the part of Catani. It was then decided

that he didn't look Italian enough for the character as devised - and was asked to try out

a variety of accents. Tate and Katzin had to really persuade the Andersons that they should

just do the obvious thing and make the character Australian. (Apparently, the producers

were afraid that American viewers would mistake Tate's accent as cockney - which actually

is quite feasible...)

We meet the other regular characters in this episode, bascially fulfilling their

duties. Paul Morrow runs Main Mission, Sandra Benes analyzes data, Dr Mathias does some

first aid - and of course, Benjamin Ouma is in charge of the Master Computer - in his one

and only appearance, he fulfils exactly the same role played by David Kano in the

subsequent episodes. There's never any onscreen explanation for Ouma's disappearance nor

Kano's replacing him. (Apparently, the actor Lon Satton didn't get along with the rest of

the cast, so was let go.) [And a small point about Paul Morrow's assistant

- nearly every source gives her name as Tanya Alexander, which possibly is what it said on

the scripts and writers' guide - but here she clearly introduces herself to Koenig as

"Tanya Aleksandriya", which sounds like a Russian name and she has an accent that could

just about pass for Russian - although I believe the actor is actually German. It would be

frankly surprising if there wasn't at least one Russian in a prominent position on an

international Moonbase.]

The Big Screen:

Science fiction has a big problem trying to predict the future - especially the

near future, which has a habit of catching up with the fiction and showing all the

predictions up as horribly inaccurate. (And here I am, talking about a tv show that's

already set a decade in the past...) In the great scheme of things, this shouldn't really

matter because science fiction isn't about accurate forecasts, it's about exploring the

concerns of the present day, by extrapolating and projecting them into an imagined future

scenario. (And as I've said before, Space: 1999 isn't really a sci-fi show anyway...)

What's significant here is that the show's technological predictions may have been

over-optimistic, but at least they make a good stab at projecting a future world.

[Compare with some of the previous Anderson shows, whose vision of the

future was essentially the high society of the sixties with better technology - albeit

often quite ludicrously Heath Robinson-style technology that just overcomplicates the way

things need to be done: the vastly elaborate method by which Virgil Tracy gets into

Thunderbird 2's cockpit, for instance. A lot of this is born out of a sort of

techno-fetishism that permeates the Anderson shows - they just love to dwell on the details

of their machines and vehicles - as well as a driving desire to get puppet characters from

A to B without having to show them actually walking. It's most obvious that the characters

are still living in the 1960s during those scenes where they're not on duty. They still

like to dress up in tuxedos to go out to restaurants or the theatre, and the most popular

records are jazz-tinged Barry Gray compositions. Can you really imagine Cass Carnaby being

a big star in the 1990s, let alone the 2060s? The trouble is that fashions, music and the

popular arts move so fast, there's no way to predict what they'll be like even five years

ahead.] By being set almost entirely off the Earth, Space: 1999 doesn't

suffer in the way UFO did when it tried to predict what we would all be wearing in

the year 1980. [In the episode Ordeal for instance, Foster goes to a party

where all the guests are hippies and beatniks, and grooves away to Beatles and Spencer

Davis Group records. It could conceivably be a sixties-revival fancy dress party. See, I'm

trying to be generous.] The Alphans are kitted out in simple but starkly effective

costumes, designed by the famous fashion designer Rudi Gernreich. Flared trousers aside -

and flares have been in and out of fashion a good few times over the years - the uniforms

fulfil their function by looking suitably utilitarian in the antiseptic confines of the

Moonbase. We don't see any off-duty outfits, so the usual pitfalls are avoided there. The

only characters seen in "civilian" clothing are Simmonds and the newscaster, both of whom

wear the standard futuristic dress code of a collarless jacket and polo-neck shirt -

(pretty much the look that was established in UFO, but thankfully a bit more

restrained colourwise).

A clever aspect of the uniforms is the colour-coded left sleeve indicating which section

the wearer is assigned to. (From the viewer's point of view, it also adds a dash of colour

to the proceedings.) So, what do the various colours mean? How exactly does Alpha's

structure work? It's not immediately clear - but let's try and piece together what we learn

from this first episode:

- At the top of the structure, obviously, is the Moonbase commander. His sleeve

colour is a dark grey - he also wears a uniquely-styled uniform with a high collar and an

additional grey stripe along his right sleeve.

- White sleeve: Medical section, as worn by Helena, Dr Mathias, and various nurses and

orderlies.

- Red sleeve: as worn by Paul and Tanya and the staff in Main Mission; so this appears

to be a control or command division. (Although there are other sleeve colours on display in

Main Mission, from which we can assume that various officers from other sections work there

too, perhaps in specialist roles.)

- Orange sleeve: as worn by Alan Carter; we'll assume this is for the astronauts.

- Purple sleeve: Security section, worn by various guards. (The security guards also wear

a special variant of the uniform: their belts have an additional strap running diagonally

over the left shoulder, presumably to support the weight of the laser gun holster -

suggesting a futuristic version of the "Sam Browne" belt worn by Army officers.)

- Brown sleeve: mostly seen on the staff in the workshop adjoining the Eagle hangar, but

also worn by Ouma - so this section would appear to cover computer programming, as well as

engineering or maintenance.

- Yellow sleeve: worn by Sandra. She's obviously some sort of analyst, so this could

perhaps be a science section. (Unlike the more clearly defined roles of the other colours,

these last two sections appear somewhat nebulous. There's mention over the intercom of the

"Service section", though I wouldn't like to speculate based on what we learn here as to

which colour that is. Hopefully, we'll learn more in future episodes.)

Of course, Professor Bergman's sleeve has no section colour at all, suggesting that he

doesn't actually fit into the Moonbase Alpha structure. I think we can infer that the base

provides facilities for visiting scientists to conduct research projects, and that's what

Victor is doing here initially. [Also, notice he tells Koenig that he "got

caught" on the base after the "virus" outbreak, implying either that there was a quarantine

imposed, or a security clampdown/news blackout. That's something else that correlates

almost exactly to the situation in 2001. Bellak's original script has television

news crews present to cover Koenig's arrival.] So it seems everyone has to wear the

uniform while on Alpha, whether they're on the staff or not - even a visiting politician

like Commissioner Simmonds. This suggests it could be a protective measure, perhaps to

preserve a sterile or anti-static environment on the base. [One of the

sillier criticisms I've heard over the years is that the uniforms are "unflattering" -

while this may be true, it makes sense for a base like Alpha to use a single utilitarian

design. You couldn't expect everyone to look good in it, so that adds a realism in itself.

These are scientists and astronauts, not fashion models.]

Having said that, it's still interesting to note how the uniformed staff and formal

command structure of Alpha differs from the moonbase seen in 2001. Clavius is

clearly a research station manned by scientists in civilian clothes, which seems likely

to be the sort of set-up we can expect if NASA and/or the ESA ever get round to building

one. [And pretty much what we see in Space: 1999's near contemporary

series, Moonbase 3.] In comparison, Moonbase Alpha seems to be more military

in nature, at least in part. For instance, Koenig is designated the Commander, not the base

director. Similarly, Alan Carter is addressed by the rank of Captain - although no one else

seems to hold a military rank. Significantly perhaps, both Koenig and Carter are astronauts

- and Space: 1999 was produced at a time when astronauts were almost exclusively recruited

from the ranks of the military. [NASA initially invited applications from

Navy and Air Force pilots - it was only on their fourth intake of Astronaut trainees that

they bothered to recruit actual scientists - of the twelve men who walked on the Moon, only

one didn't hold a military rank.] In 1999, does the military retain closer control

over the space programme? Are the scientists working on Alpha seconded to the military

rather than the other way around? It seems a far cry from the ideals of the Apollo project

("we came in peace for all mankind"). [There will certainly be evidence of

a strong military aspect to the space programme later on (q.v. War Games). I think

this probably stems from the show's origins as a planned revamp of UFO - but the

notion made it through to the very first draft of the series format, in which Alpha was

still conceived as an international base to defend the Earth against alien attack.]

We see a glimpse of 1999's space programme at the beginning of the episode - the Meta

Probe and the Space Dock. The probeship is a long, narrow vessel with large engines at the

end. (You won't be surprised that it seems vaguely inspired by the Discovery from

2001.) There are two radiating panels attached to the sides, and the usual insectoid

Eagle cockpit. The space station demonstrates a rare example of the series rejecting the

imagery established by 2001 - intead of the movie's space wheel, here we have a

complex of interconnected cylindrical modules, not too dissimilar to the real life

International Space Station - though probably much larger in scale. The series was made

when Skylab was a current project - the US space station was converted from the third stage

of a Saturn V rocket. The modules of the Space Dock also seem to be rocket booster stages,

a logical interpolation on the part of the modelmakers of the then-current technology.

Conversations between Koenig and Simmonds reveal that the running of the space programme

is dogged by politics. Simmonds attempts to cover up the potential disaster resulting from

the incapacity of the Meta Probe astronauts - not even telling Koenig about the severity of

the illness. He's worried about a forthcoming meeting of the International Lunar Finance

Committee which he fears will cut off further funding if they realize the Meta Probe could

be a failure. This is a believable picture of the way the space programme might work in

reality, and far more cynical than previous Anderson series where the advance of technology

could never have been halted by something as mundane as money. Thunderbirds and its

ilk were created at a time when the Wilson government was promising "the white heat of

technology", and NASA was forging ahead in a race to the Moon that Kennedy had initiated in

a fit of cold war defiance. By the mid-seventies, Kennedy's dream had been fulfilled.

Congress had cut back NASA's funding, and the Apollo project was curtailed.

[These things come and go. At the time of writing, space exploration seems

to have some political significance again, and NASA have been granted the funding to press

ahead with the Constellation Project, with the aim of getting back to the Moon within the

next 20 years. But even now, there are concerns about the cost, and President Obama has

already requested a review of the project his predecessor instigated only a few years ago.

So it might yet all come to nothing. Just a decade before, NASA were having to scrabble

around looking for funding. You may recall the huge blaze of publicity that surrounded the

discovery of a meteorite that might have proven the existence of microbe life on

ancient Mars. That seems like the sort of stunt Commissioner Simmonds might have

pulled...]

So, Moonbase Alpha exists as a scientific research station, a staging post for space

exploration missions; and also serves to monitor the nuclear waste dumps on the far side of

the Moon. Simmonds says, "Atomic waste disposal is one of the biggest problems of our

times." In the real world, nuclear waste has never been such a major issue - yes, it's

dangerous and has to be treated with care, but it's hardly of the volume where we have to

think about sending it to the Moon! In the world of Space: 1999, it certainly appears

that nuclear energy has become the world's major power source. (This is in keeping with

earlier Anderson series, which always postulated a labour-saving nuclear-powered future.

Again, this is born of that "white heat of technology" ideal.) Space: 1999 was

created at a time before the public became aware of the inherent dangers of nuclear power -

Three Mile Island was yet to happen. As things have turned out, nuclear power hasn't

supplanted oil or gas as the major source of electricity, and it probably won't for many

years to come - if ever. [Although with mineral resources clearly

dwindling, something will have to be done sooner or later - unfortunately, the very word

"nuclear" comes laden with so many negative connotations in the public mind, politicians

are wary about committing to the building of new power stations. I think widespread power cuts

will be bigger vote-losers in the long term, but most governments can only see as far ahead

as the next election.] Despite thus embracing the nuclear age dream, Space: 1999

shows a certain amount of caution and wariness in raising the question of the disposal of

nuclear waste. And it's significant that complacency over the issue is the apparent cause

of the eventual disaster. Remember, this was still some years before the general public

became aware of environmentalist ideas, and long before politicians started to jump on the

bandwagon. We can only imagine that in 1999, public concern will no longer allow the

storage of nuclear waste on Earth - which seems quite an accurate prediction of the way

our attitude to the nuclear industry would change.

One thing that's immediately apparent - the interior of Moonbase Alpha has normal Earth

gravity, or a very close approximation. This extends even to distant buildings, like the

nuclear waste monitoring depot - but not apparently anywhere out on the lunar surface.

(The show makes a good attempt at depicting astronauts moving in one-sixth gravity - using

a combination of slow motion filming and flying wires, these scenes bear comparison with

the way the astronauts moved in the real television pictures of the Apollo Moon missions.)

Having normal gravity makes life easier for the inhabitants of Alpha (not to mention for

the show's producers!) - and also provides essential health benefits: living in prolonged

low gravity causes the human body to produce less calcium, with the result that bones

become weak and brittle, and much more prone to fractures. This is still a problem that

needs to be countered before long duration space missions can become a reality. So, how is

the gravity generated? There is an artificial gravity system, which seems to involve

magnetic fields in some way (since it's necessary to have a device specifically to monitor

the system's magnetic output). [This may well derive from the first

mention of artificial gravity in science fiction, in Olaf Stapledon's Last and First

Men, which vaguely described the system as being "based of the properties of the

electro-magnetic field". If you think that's just a coincidence, there's a lot of Stapledon

influence coming up in the series, so it's likely that someone on the writing staff had

been reading his books.]

The show falls down somewhat in its depiction of computer technology. Fortunately, we're

spared the usual 1970s image, the giant banks of whirling tape spools. [As

seen for instance at SHADO HQ in UFO - to be fair, these probably looked state of

the art in 1969.] Indeed, Space: 1999 is careful not to show us the precise

nature of Alpha's data storage. What we see are black and white wall units in Main Mission,

which could well suggest the processor units of a large-scale mainframe computer, exactly

the system a complex like Alpha would need to run the environmental processes and maintain

back-up data storage. It's the user interface that seems wrong to the modern eye. There are

small keypads and monitors set into the computer banks, implying that programming and data

input is done in situ. Although some of the desks in Main Mission have a keyboard, there is

no monitor or mouse. Whereas the modern office environment would put a pc on each desk,

perhaps connected to a network server, on Alpha there seems to be only the one Computer.

(Actually, you could just about believe that the keyboards are thin client terminals

running off the Computer's central server, if it wasn't for the lack of monitors - the crew

just can't interact with the Computer to run normal desktop applications - they can only

input data and wait for it to make pronouncements.) [It's almost as if the

Computer is one of the oracles of myth, dispensing its wisdom as divine gifts (in the shape

of tickertape printouts or messages on the big screen). Taking the analogy further, Ouma

(and later Kano) is the high priest, the only one allowed to have full communion with

it.] This is a series made before the home pc revolution - before the computer

became accepted as merely a useful office tool, and was still seen as a remote and powerful

technological monster. (The all-powerful, unstoppable computer is a common trope in the

sci-fi of the period: some good examples are The Forbin Project, Demon Seed,

Doctor Who's WOTAN or BOSS - and of course, 2001's HAL. Alpha's Computer

definitely fits into this pedigree.) Is it an artificial intelligence? It's hard to tell.

Certainly, it seems to have no personality to speak of, speaking in a bland, emotionless

female voice. The only time it's asked to make an actual evaluation here, it refuses, and

bats the question back to Koenig.

The Alpha communication system provides a tv monitor on every wall, desk and corridor

post. In an age where video-conferencing is a reality, this seems quite a reasonable

prediction. (It would be nice if the monitors were colour and flat screen, but you can't

have everything.) Every panel and post also has a time display - rather oddly, there's an

old-fashioned analogue clock alongside the more expected digital display. This seems a

redundant duplication of systems.

Everyone on Alpha is issued with a personal commlock. (Quite literally, in fact. Both

Koenig and Simmonds are handed one as soon as they arrive on the base.) This is a perfectly

feasible device - the technology could easily be achieved today - it would just be a case

of adapting a mobile phone to carry a video signal. (Not widely available perhaps, but at

the time of writing, such devices are now starting to come onto the market.) Within the

confines of the Moonbase, we can presume that a transceiver network picks up all commlock

signals and directs them to the correct recipient. The "lock" function of the commlock is

also pretty commonplace today. We've all seen electronic remote controls for opening garage

doors, or swipe cards to let authorised personnel into secure areas of corporate buildings.

Combining such everyday functions in a single device is practical, and a good design

decision.

The sick astronauts are kept on life support in the Medical Centre. This consists of a

single unit placed over their chests which seems to be monitoring their life signs - with

no visible wires, tubes or drips. Medical technology seems to have come along considerably!

The Computer collates the information received, and is able to pronounce when brain death

has occurred. Its announcement that Astronaut Sparkman's body functions are being kept

going only by the machines is all Helena needs to make the decision to turn off the life

support. She doesn't consult with Sparkman's family - or (if there is no family) with some

kind of medical ethics board. She acts merely on the basis of Computer's conclusion; she

doesn't consult with her colleagues or refer the decision to anyone else - not even to

Koenig. This tells us that doctors in 1999 have very great and unilateral powers to make

decisions of life and death. It also implies - since with the constant monitoring and

computer reporting, there's no way that Helena could do this without the fact being

recorded - that she has no expectation of any legal comeback from her decision.

The last signal the Alphans pick up from Earth is a news broadcast reporting on the

gravitational effects and seismic disturbances on Earth following the breakaway. It's

nothing like a modern news programme - just a single presenter sitting in a plain studio -

there are no flashy graphics, scrolling headlines, images displayed behind the newsreader;

no on-the-spot reporting beamed live by satellite. [I hesitate to say that

something "dates" a show, because television obviously reflects the times in which it is

made - but this is one moment that really takes me out of the drama. (Still, 2001 didn't do

any better in this regard. There's a television interview with the Discovery crew

that would have seemed old-fashioned even in 1968.)] The newsreader refers to

earthquakes taking place in Yugoslavia. It was more usual for journalists in 1999 to refer

to the region as "the former Yugoslavia", following the break-up of the communist republic.

(However, this is technically not an error - the remaining non-secessionist states of

Serbia and Montenegro continued using the name Federal Republic of Yugoslavia until 2003.)

Meta is a rogue planet that has entered our solar system. It is passing just close

enough to the Earth for a precisely timed mission to reach it and make a manned landing.

An unmanned probe takes close-up pictures of the planet, revealing it to have an atmosphere

of impenetrable blue clouds, and also that it is transmitting a regular, repeating signal -

which Commissioner Simmonds takes as evidence of intelligent life on Meta. (Though again,

this could be his usual spin on the news, making a discovery seem more significant than it

is to try and justify the continual funding of the space programme. A regular radio signal

need not necessarily be evidence of intelligent life - the planet could have an unusual

rotating magnetic field for instance.) Unfortunately, we never find out any more

about Meta, since the problems on Alpha scupper the probe mission.

Human Decision Required:

There are a number of approaches to producing a show's opening episode. You want to

be able to introduce the set-up and format, but at the same time need to avoid swamping the

viewer with information. One method is just to throw as much of the show's concept at the

screen and hope some of it sticks. A more sensible approach is to start with a newcomer

entering the scenario, and to discover it as they do. And this is what we see here: we

follow Koenig as he arrives and takes command of the base, then meets the main characters

one by one. [UFO by contrast went for the "see what sticks"

approach, showing us one piece of SHADO hardware after the other. The nominal hero of the

first episode is Captain Carlin, who loses his sister in the teaser, and finds out what

happened to her at the conclusion. Unfortunately, the script doesn't follow Carlin's

journey all the way through - if we'd seen how he met Straker and joined SHADO following

his sister's disappearance, it would have given the story some dramatic cohesion.

Ironically, UFO also made a stab at the "newcomer" approach, when they devoted an

episode to introducing the character of Foster, following him as he delved deeper into

SHADO. You can't help but think this would have made a better opening episode. Switch them

around, show Foster joining SHADO - then introduce all the technology in episode 2. It's

interesting to note that in the series novelization, this is exactly what happens.]

Having set the scene and established the mystery, the episode proceeds to pile on the sense

of impending doom, successfully glossing over any implausibilities by virtue of simply not

letting up. The dramatic build-up leads to a conclusion that doesn't disappoint.

Koenig has obviously been stationed on Alpha before (q.v. Dragon's Domain). He's

familiar with many of the personnel, and seems to have been a popular person as is apparent

from the warmth with which he is greeted. He and Victor clearly know each other well. (His

relationship with Helena, whom he hasn't known before, is initially frosty however.) Koenig

is an interesting character. He's been selected as commander precisely because Simmonds

sees him as the man to get the Meta probe mission back on course - so we might infer that

his previous experience in space exploration makes him ideally suited to this task -

whether he'd have remained as Alpha commander after the Meta probe is open to question. It

could well have been intended as only a temporary assignment, had events not unfolded the

way they did. Those qualities that make him the man to get the mission launched (determination,

technical expertise) don't necesarily equip him to run a scientific research station - nor

yet to lead a desperate struggle to survive in the face of the vast unknown. (That's obviously

a role for which no one can be prepared.) Koenig demonstrates almost straight away that he's

perhaps not usual command material, by personally taking an Eagle out to survey Area One,

and nearly getting himself killed in the process. (Helena rightly criticizes him for this

stunt.) A former astronaut, a man of action used to getting things done by direct

intervention, might be expected to do this - and maybe that's why Simmonds appointed him,

because he knew he'd ride roughshod over problems and objections - but they aren't

necessarily the actions of a commander, who should be making decisions and delegating

the dangerous tasks to the appropriate members of his staff. [Again, you

can contrast this with UFO, in which Straker is very much the commander who stays

back at HQ and makes the tough decisions, while Foster went out and did the action stuff.

That's clearly a more believable military set-up - you don't put the commanding officer

right on the front line.] It's notable that Koenig chooses to put the safety

and lives of others over the demands of the mission - abandoning the Meta probe early on

whilst the deaths remain unexplained, then concentrating on the problem in the Disposal

Areas. (So perhaps he's not the man Commissioner Simmonds thought...) It seems that similar

concerns dictate his first big command decision - to abandon all hope of returning to Earth

on the grounds that they're more likely to survive by remaining on Alpha. (Though it could

be argued that far from being a tough choice, this is in fact the easy option - better to

stay where they are than embark on the more dangerous course of trying to get back home.)

What's clear is that Koenig commands a great deal of loyalty and respect from many of the

Alphans - no one questions his decision. (Perhaps this is another legacy of his astronaut

days: that he's thought of as something of a hero.)

In many ways, the conception of this episode was driven by the need to have a huge

explosion. At the insistence of the show's US backers, it needed to be built into the

format that the Moon was completely cut off from Earth. [At the time,

interest in the Moon and space exploration generally was riding high; also, the more

character-led (or "soapy" if you like) Earthbound episodes of UFO had been perceived

as less popular than those set on the Moon - the backers wanted a cast-iron guarantee that

they wouldn't do any more stories about divorce and children dying...] The earliest

attempt at a pilot script, written by the Andersons themselves, had devised the show as

more of a children's programme - a half hour format which still featured aliens attacking

the Moon. The idea was that the aliens would "reduce the Moon's gravity" and cause it to

shoot off into space. [If this show had been produced, of course, it's

unlikely I'd be here thirty-five years later writing about it.] As the format was

retooled and reshaped, the producers eventually arrived at the idea of the massive nuclear

explosion. (Christopher Penfold has described this as a "eureka" moment.) As I've said,

this was written at a time before the environmentalist lobby had gained much political

capital, and was still seen as a fairly fringe (or even crank) movement - though concerns

over pollution in general were starting to emerge in the public consciousness. So in that

regard, the series is in tune with the times, and even somewhat forward-thinking. It's

certainly one of the first times that the word "atomic" is used in a popular sci-fi series

with a negative connotation. (It's as if those carefree 1960s days of nuclear-powered

wonder have to be paid for by a new cynicism.) Christopher Penfold seems to have had

particular concerns in this area. In 1982, he wrote a series called The Brack Report,

about a scientist commissioned to investigate the dangers of the nuclear industry and the

possibilities of alternative energy sources.

Space: 1999's predictions of technological development may seem far-fetched - this

surely results yet again from the influence of 2001. Interpolating from the state of

the space programme in 1968, Kubrick and Clarke presented a vision of what it would be like 33

years in the future. (And at the time, that vision was feasible. A writer as scientifically

literate as Arthur Clarke would never have allowed anything that stretched credibility. It

was generally supposed that the Apollo project would continue, and NASA proceed smoothly to

the next stage of space exploration.) Unfortunately, by the time Space: 1999 came

along, those predictions were starting to look a little too optimistic - the funding cuts

and subsequent curtailment of the Apollo programme had set back everything that NASA might

have hoped to achieve by the century's end. This didn't stop Space: 1999 from picking

up the setting of 2001 virtually intact, and thereby presenting a future far more

advanced than we could reasonably hope to expect. (And then to compound it, they go and

create even more far-fetched ideas, like laser beam weapons...) It's true that Gerry

Anderson has always maintained an optimistic view of the future, and of technological

progress - and since this show has a healthy streak of pessimism running through it

already, perhaps we can forgive these positive predictions for the sake of some balance.

There's also a good psychological reason for setting the show in 1999: it ensures that the

series is still happening within the twentieth century, and within the lifetime of most of

the viewing audience. It's important that the characters are more or less contemporary

people, as the series is essentually about ordinary people in extraordinary situations.

The episode opens with a caption proclaiming that we're on the "dark side of the Moon",

As anyone who knows a bit of rudimentary astronomy will tell you, there is no dark side. The

Moon rotates once in a lunar month, so the entire surface has two weeks of day and two

weeks of night. The caption is in fact accurate for the opening shot, since the Sun is

distant and only illuminating a crescent. Unfortunately, Paul Morrow twice refers to the

"dark side" as if it's a permanent geographical feature - although Ouma more accurate calls

it the "far side". (I have to wonder whether the title of Pink Floyd's mega-selling album

had stuck in someone's head when the episode was made...)

When Koenig suggests that the back-up crew will have to be made ready to fly the Meta

probe, Alan Carter rejects the suggestion with the rather cryptic comment: "We can't do it

- calculations, co-ordinates..." It's a blunt dismissal that really offers no explanation

of what his objection is. (Koenig certainly doesn't question it.) Is Alan saying that the

back-up crew aren't properly prepared or trained for the mission? The whole point of having

a back-up crew is that they can step into the shoes of the primary crew at a moment's

notice. Helena confirms that they have been through the same training programmes, indeed

lived identical lives to Warren and Sparkman. There shouldn't be a problem.

Can a rogue planet like Meta, travelling through space between solar systems, without

the heat of a sun to sustain it, support life? Or would any atmosphere it did have be

frozen solid? Since Moonbase Alpha is proposing to land a spacecraft there, it would seem

Meta is a terrestrial-sized planet, rather than say a gas giant. The planetary scientist

David Stevenson has theorized that an Earth-sized interstellar planet with a thick hydrogen

atmosphere could insulate itself against heat loss, such that the planet's own geothermal

energy could provide enough heat to melt ice and allow the formation of oceans, as well as

ocean-floor volcanism. Now, it's possible that life can exist in these conditions, even

without sunlight. (In the depths of Earth's oceans, entire self-contained ecosystems can

exist around hydrothermal vents in the ocean floor. New and exceedingly weird species have

been discovered in this environment.) But this can't possibly be "life as we know it" as

Simmonds suggests.

Even assuming that nuclear energy is more widespread than it is in real life, and that

the decision has been made to get nuclear waste off Earth - we have to ask whether sending

the waste to the Moon is really a sensible solution? Wouldn't it make more sense to

load it into a rocket and blast it off into deep space? Then we could just forget about it.

Taking it to the Moon requires more effort and more fuel. The waste has to be unloaded and

stored; and then constantly monitored to ensure it remains safe.

The build-up of atomic waste is producing unprecedented levels of magnetic energy, and

this is responsible for the "illness" affecting the base - diagnosed by Helena as an

unusual form of brain damage. A major health scare in recent times has been the fear of the

unknown dangers of electromagnetic radiation from mobile phones. (This is radiation in the

microwave part of the spectrum.) It's an area that clearly needs more informed research -

although the World Health Organization has stated that the alleged risks are "unlikely" -

but forms of cancer and brain damage (including disorientation and memory losses) have been

cited as possible outcomes of prolonged exposure. Helena also states that the effect is

similar to "classic" radiation damage, and that a malignancy (tumour) erupts in the brain.

The other physical damage to the victims, such as the disfigured skin and eye cataracts, is

fairly consistent with the long term effects of radiation poisoning - although in reality,

such damage usually becomes apparent ten or fifteen years after radiation exposure,

not on the short time scale seen here. Still, the basic science is accurate enough. The

problem with all this is that the writers haven't really decided what's causing what

damage. In order to establish their mystery, they present all the symptoms of radiation

poisoning - then reveal that the problem is the previously unexpected rise in "magnetic

energy": if that means microwave emissions, it could conceivably have caused the brain

damage, but not the other physical effects. But if there was no radiation leakage, what

caused those first "classic" radiation symptoms? It doesn't seem to add up. There's also

the question of whether nuclear waste could produce that magnetic energy in the first place.

Microwave emissions are at completely the opposite end of the spectrum from gamma radiation,

which is what you'd expect nuclear waste to give out. I'll come back to that.

The standard position of the nuclear industry is that radioactive waste cannot explode.

At the time of original broadcast, some critics even used this argument as further "proof"

of the inaccuracy of Space: 1999. In actual fact, if it's not stored properly,

nuclear waste can indeed heat up and explode. This happened as early in 1957 at a Russian

nuclear fuel reprocessing plant near the town of Kysthym. A waste tank's cooling system

failed, and the waste inside heated up and exploded, spreading radioactive material over an

area of 15,000 square kilometres. This is reckoned to be the worst ever nuclear accident

before Chernobyl, but it was hushed up by the Soviets for years. This wouldn't have been

known to the writers of Space: 1999, so the depiction of a massive heat increase

inside the nuclear disposal areas was both realistic and quite prophetic given the denial

of such risks by the nuclear industry at the time. (As Koenig says, heat without atomic

activity was thought inconceivable then.) But how does the magnetic energy cause the waste

dumps to heat up? Well, if we return to the idea of magnetic fields causing microwave

emissions, then one possibility is that the microwaves disrupt the cooling systems in the

storage areas. So far, so good. The difficulty comes with the nature of the explosion.

Spent nuclear fuel is called that because there's no releasable atomic energy left inside

it. So even if it does explode, that explosion will be non-nuclear in nature. It will throw

out radioactive contamination, but there's no fissile material left to cause a nuclear

chain reaction such as we see this episode.

Another criticism that's been made: if the nuclear waste dump is on the far side of the

Moon, then logically the explosion ought to send the Moon hurtling towards Earth, not away

from it. But this supposes that no other forces are acting upon the Moon at that moment.

And there's one very obvious force at work here: the gravity that binds the Moon to the

Earth in the first place. As the explosion pushes the Moon towards the Earth, the force of

the Moon's original orbital motion will still be acting upon it. This would keep the Moon

from actually colliding with the Earth - instead it would spiral in towards the planet, to

make a very close transit before shooting off into space on the other side. (In fact, this

was even suggested at the time by no less a luminary than Isaac Asimov - he was generally

critical of Space: 1999, but conceded this point as one of dramatic necessity.) Such

a close transit of Earth would give rise to abnormal tidal effects. The news report of

gravity disruption and resultant seismic disturbances would fit quite well with that

scenario.

The end of the episode is virtually a cliffhanger, implying that the Moon is fast

approaching a close transit of Meta, and that the Alphans may find their future there.

This is not followed up in any subsequent episode, so the Meta storyline is left hanging,

without resolution. (We may have to assume that the Moon passed by Meta. Maybe the Alphans

attempted a landing - more likely they were still trying to pick up the pieces following

the disaster, and trying to salvage and repair the Eagles that crashed during the

breakaway. Whatever happened, their journey continued - and they never mention Meta

again...) I think the fact that Meta remains unseen and mysterious adds to the ending - it

doesn't matter that we don't see what happens there. It's not a literal place so much as

it's a symbol, representing all the strange and wonderful planets the Alphans are going to

encounter on their voyage. (The very name means "beyond", and hints at the

metaphysical journey ahead.) So when Koenig says "maybe there", he's talking not

just about Meta, but about the whole unknown cosmos...

On the surface, everything that happens in this episode seems fairly straightforward.

But let's consider those remaining scientific mysteries. How does the nuclear waste

generate magnetic energy, and how does that create a fission chain reaction? What if the

nuclear waste isn't the cause at all? (Let's say Victor's right about all the effects, just

not the origin.) It always strikes me as too much of a coincidence that all this should

start happening just as a mysterious new planet enters the solar system - and starts to

beam out indecipherable signals. Now consider: we'll learn later that there's an

ordained purpose behind the Moon's breaking free from orbit (q.v. The Testament of

Arkadia). We also discover that rogue planets can act as catalysts for universal change

(q.v. Collision Course). So here's my hypothesis: the planet Meta is the cause of

all that happens to Alpha in this episode. Its strange repeating transmission is not an

attempt to communicate with Earth; it's the source of the magnetic radiation that affects

the base. The "brain damage" is an unfortunate side effect - its real purpose here is

to shut down the cooling systems and make the nuclear waste explode. At the same time, by

some unfathomable process, it re-energizes the spent nuclear fuel into fissile material.

(Now, that might sound rather vague and magical, in which case I could invoke Clarke's

third law: "Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic".)

[It's easy to regard that maxim as something of a universal get-out

clause, but this is Arthur C Clarke speaking - the inventor of the communications

satellite, as they loved to point out on each edition of Mysterious World. What he

suggested is actually a very powerful literary device. It means that you can depict the

technology of advanced civilizations without having to define and explain it, simply

because it is inexplicable, way beyond our current understanding. It's far

better to leave these things as mysteries than to try and invent cod pseudo-science and

technobabble.] There's certainly evidence within the episode of unusual radiation

effects - the "virus infection" affecting the probe astronauts and waste disposal workers

- yet nothing that can be detected by the instruments on Alpha.

So what seems to be the result of human error and complacency, might

actually be the intervention of higher powers. If we accept this, then the arrival of Meta

has a much deeper significance - perhaps its course into our solar system has been

deliberately engineered by those higher powers seeking to guide the Alphans' destiny.

What seems unexplained and even mystical might simply be the application of frighteningly

advanced technology. The ability to re-energise spent nuclear fuel might just be the tip of

the iceberg: perhaps "they" can warp space-time or decrease the Moon's inertial mass (which

would immediately counter two of the more persistent criticisms about the science of the

breakaway) - but the great thing is, none of this is explained in the series. It doesn't

need to be. This application of Clarke's law suggests a reason why the Moon isn't simply

destroyed, but is somehow launched relatively intact on its space odyssey - as Victor later

speculates (q.v. Black Sun). It's all part of the scheme of things...

Next episode

Back to Episodes of the first series

Back to Site index

Created by

Andrew Kearley.

Please email me with your

comments and suggestions.

In fact, I'd go further than that and suggest that Space: 1999 is a conscious attempt to create a television equivalent to 2001. (Even the title is practically the same!) [And it was this very fact which led Stanley Kubrick, in one of his more fevered moments, to seriously consider suing the producers for damages.] It's easy to spot those elements of the first series which derive in some way from that movie: visual cues such as the exterior design of the Moonbase and the brightly-coloured spacesuits; the style of the special effects (which effects designer Brian Johnson was deliberately attempting to reproduce); and such stylistic and philosophical conceits as the underplayed characterizations, and the theme of humans forced to confront the mysteries of outer space head on, at the mercy of inconceivable higher powers who shape their destiny. These borrowings, whether conscious or otherwise, are not necessarily a bad thing. They say if you're going to steal, you should steal from the best! 2001 had completely changed the look of science fiction, and redefined the audience's conception of outer space. [This huge leap forward in the visual aesthetic completely overwrote the look of 1950s films by directors like George Pal (which had themselves influenced the look of earlier sci-fi television - you can't watch the launch sequence of Fireball XL5 without thinking of When Worlds Collide for instance). We wouldn't see anything as radical again until Star Wars.]

The credited writer of Breakaway, George Bellak, was one American writer who did come to Britain to work on Space: 1999. Originally hired as a script editor to work alongside Penfold, Bellak left the production soon after completing this script (by all accounts, there was something of a clash of personalities between him and Anderson). With only this one script credit to his name, Bellak is something of an unsung hero of Space: 1999. Christopher Penfold gives him credit for much of the show's style and philosophy. Working together, the two writers refined the format and wrote the series bible. Following Bellak's departure, Christopher Penfold rewrote the opening script. The original version entitled The Void Ahead was intended to fill a ninety minute slot, rather than the standard television hour of the finished episode. Though it essentially tells the same story, many of the supporting characters had yet to finalized; there were also a number of additional scenes which filled in character detail - most notably a sequence where Gorski visits Koenig to rubbish Helena's theories about the "infection"; and a scene where Helena explains the reason for Gorski's animosity - that he made a pass at her which she didn't reciprocate. I'd always wondered whether these scenes were cut at script stage, or filmed and then dropped in editing. If the latter, it might explain why an actor of Philip Madoc's calibre was engaged as Gorski, a character who amounts to a twenty-second appearance in the finished episode.

It's certainly been reported that the shooting of Breakaway far exceeded its original schedule. Lee Katzin was an American director brought in at the insistence of the US backers; he had plenty of experience in series television, including technically complex shows like Mission: Impossible (on which he'd worked previously with Landau and Bain of course), so was considered a safe pair of hands to launch Space: 1999. No one seems quite sure why he made the unprecedented decision to shoot excessive coverage of every scene, with multiple angles and reaction shots. (I like to think that he became so enthused by the concept of Space: 1999, he forgot he was shooting television and decided to treat it as a feature film.) Katzin ended up with a rough cut reportedly some two hours long. Seemingly, it was left to Gerry Anderson to shoot some pick-ups and then edit the whole lot down to the required fifty minutes. Whatever the truth of the matter, the tension and pacing of the finished episode is remarkable. [Whereas Anderson's true talent as a producer has always been as a manager, having the ability to hire the right people to do the job, I think his real creative skill has been as an editor and director.] It would be interesting to see some of Katzin's discarded footage - (presumably those scenes of Gorski among them) - but as no deleted scenes package turned up on the DVD, it seemed unlikely that the rushes had survived. And yet, amazingly, in November 2010, several reels of audio tape surfaced containing raw studio sound from the filming of Breakaway. [Which just goes to show, you never know what might still be out there somewhere.] Although obviously lacking the visuals, these recordings offer a fascinating insight into a work in progress. There are a lot of dialogue fluffs and actors missing their marks, and almost continual retakes - plenty of evidence of the huge amount of coverage that Katzin shot. As well as scenes that never made it to the final cut, many of the other sequences are quite different to what we eventually saw, indicating that much of the finished script was amended during production. There's also plenty of material that's simply unnecessary, repetitive and saggy scenes that would have slowed the pace right down - there's no doubt that the decision to cut was the right one. (And yes, in answer to my question, there are several takes of that scene between Gorski and Koenig, the characters exuding a mutual loathing.) [These audio clips have been posted to Youtube, and are well worth seeking out - do a search there for "Space 1999 rare audio".]

As well as the usual passenger and freighter modules, the Eagle that shuttles Commissioner Simmonds to the Moon has a unique orange pod, perhaps denoting that it has special VIP facilities.

The show's typography is of particular interest. Aside from the specially-designed title logo, all the titles and credits are in the Futura Medium font. Like so many of the best typefaces, this was designed in Germany in the 1920s - it's a sans serif font based on geometric shapes. Its sleek, elegant simplicity make it very much part of the look of the show. Interestingly though, the original intention was to use the variant Futura Black font for the series title logo - a rather severe stencil-form typeface, it's retained for the "This Episode" and "September 13th 1999" captions during the title sequence - and the Braggadocio font for the cast and crew credits. This was apparently abandoned because it rendered many names difficult to read. [And that's absolutely true: the capitals aren't too bad, but the lower case letters in particular can be problematical. It's no surprise it was dropped. What is odd though is they decided to go with Braggadocio in the first place. Though it's superficially similar in appearance, Futura Black is a lot cleaner, more elegant and easier to read; since they were using Futura Black in any case, why not use it throughout instead of mixing typefaces like that?] Perhaps significantly, Futura was the official font adopted by NASA for the Apollo project; it was also used in the opening credits of - you've guessed it - 2001.

The Big Screen:

Science fiction has a big problem trying to predict the future - especially the

near future, which has a habit of catching up with the fiction and showing all the

predictions up as horribly inaccurate. (And here I am, talking about a tv show that's

already set a decade in the past...) In the great scheme of things, this shouldn't really

matter because science fiction isn't about accurate forecasts, it's about exploring the

concerns of the present day, by extrapolating and projecting them into an imagined future

scenario. (And as I've said before, Space: 1999 isn't really a sci-fi show anyway...)

What's significant here is that the show's technological predictions may have been

over-optimistic, but at least they make a good stab at projecting a future world.

[Compare with some of the previous Anderson shows, whose vision of the

future was essentially the high society of the sixties with better technology - albeit

often quite ludicrously Heath Robinson-style technology that just overcomplicates the way

things need to be done: the vastly elaborate method by which Virgil Tracy gets into

Thunderbird 2's cockpit, for instance. A lot of this is born out of a sort of

techno-fetishism that permeates the Anderson shows - they just love to dwell on the details

of their machines and vehicles - as well as a driving desire to get puppet characters from

A to B without having to show them actually walking. It's most obvious that the characters